Nour stands shivering in the cold afternoon light in the courtyard, not from cold, but from fear.

She came wearing her thick winter coat to complain to the men of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, the new de facto rulers of Syria, and the new law in the city.

She began to cry as she explained that three days ago, shortly before 9 p.m., armed men in a black truck arrived at her apartment in an upscale neighborhood in Latakia. She, her children and her husband, an army officer, were forced into the street in their nightclothes. Then the militant leader moved his family to her home.

Darren Conway/BBC

Darren Conway/BBCNour – not her real name – is an Alawite sect, the minority from which the Assad family descends, and to which many of the former regime’s political and military elite belong. The Alawites, whose sect belongs to Shiite Islam, constitute about 10% of the Syrian population, and the majority of them are Sunnis. Latakia is located on the northwestern coast of the Mediterranean Sea in Syria and is their stronghold.

As in other cities, a range of different rebel groups rushed to fill the power vacuum left by the departure of Assad’s soldiers from their positions. The regime has exploited sectarian divisions to maintain its grip on power, and now the Sunni Islamist group Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham has pledged to respect all religions in Syria. But the Alawite population of Latakia is afraid.

Some people have not left their homes since the regime change because they fear there will be a reckoning, and that they will have to pay a high price to support the old regime.

Nour shows surveillance footage from her apartment to 34-year-old Abu Ayoub, the public security commander for Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham. The film shows a group of bearded fighters, some wearing baseball caps and others in military uniform, on her doorstep.

Quentin Somerville/BBC

Quentin Somerville/BBCIt says they are not from Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, but from another group of rebels from the northern city of Aleppo.

“They broke down the door,” Nour tells Abu Ayoub. “There were 10 armed men at our door and 16 others waiting in the street in three cars.” Most of his men are from Idlib and Aleppo, where Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham and allied rebel factions were based before launching the offensive that ousted Assad three weeks ago. Dressed in military uniform and holding rifles, they stand and listen intently as she describes how the family’s belongings were thrown into the street.

Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham was once allied with Al Qaeda, and remains banned as a terrorist organization by most Western countries, although the UK and US say they are in contact with the group. Within weeks, it went from enemy of the state to the law of the land. Abu Ayoub and his men adapt to changing roles from revolutionaries to policemen.

Nour is just one of a long line of complainants who have filed complaints with the Public Security Center. The base, the former headquarters of military intelligence in the city, was perhaps the most terrifying place in Latakia. Now the place is a mess, with radios and broken equipment scattered all over the yard. Torn pictures of Bashar al-Assad lay on the dirt.

A man joins the queue to file complaints. He has a black eye, broken ribs, and his shirt is torn and stained with blood. He says that men from Idlib stormed his apartment.

Darren Conway/BBC

Darren Conway/BBCHe says: “Some of them were civilians, and some of them were wearing military clothes and were masked.” “They beat my daughter and pointed weapons at my son’s head. They stole money, they stole gold.”

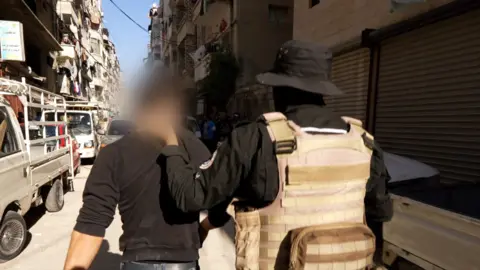

Every call here is a show of force, especially with the presence of so many armed groups in the city. Under the direction of the man’s son, HTS security forces drive their car into a slum, driving through a series of back streets, junkyards and downtowns.

Armed police take up positions along the street and at the entrance to the apartment. They brought two suspects back to the station for questioning.

But they barely have time to dispose of their weapons when there is another complaint, a dispute over gas bottles that results in another man being beaten.

He says that three men pulled their weapons on him.

Darren Conway/BBC

Darren Conway/BBCAnother car race into a busy commercial and residential district. When the police drag a suspect into the street – his face still bloodied from the previous fight – local women come to their balconies and shout “Shabiha! Shabiha!” They accuse the suspect of being a member of a shadowy militia force, mostly Alawite men, who did the dirty work for the Assad regime.

Since its swift sweep to victory across Syria, the Islamic State Headquarters for the Liberation of Al-Sham has pledged to maintain peace and protect all minorities in the country. Every day, Abu Ayoub must fulfill this pledge.

He adds, “Some infiltrators into the revolution, some saboteurs, and some weak-minded people are taking advantage of the situation in the areas that were recently liberated.”

Abu Ayoub admits that the situation in the city was “a bit chaotic” but turns his attention to Nour. “We are here now, we were not here when the army left. We were first in Damascus and then we came. They are thugs, we will expel them from your house. We will return your property. I have your word,” he said. With this, he ordered his men to get into their pickup trucks, and with sirens sounding, they headed to the apartment.

Latakia is a liberated city. Last Friday, tens of thousands of people from all sects gathered in the streets to celebrate the fall of the Assad family. In one of the city’s squares, they sat atop the pedestal where a statue of Hafez al-Assad, Bashar’s father — who ruled for 29 years before his death in 2000 — once stood, and joyfully waved the flag of a free Syria.

The message that day was one Syrian unity without sectarian division. But after half a century of authoritarian rule from a regime that stoked sectarian hatred and warned that Alawites would be massacred if they lost power, this is an adjustment to say the least.

On Saturday, three Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham fighters were killed, and 14 others were wounded outside the city, in what it said was a gun battle with a criminal gang. Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, which is trying to maintain calm, claims that there was no sectarian element in the attack.

On the way to Nour’s apartment, the Tahrir al-Sham convoy speeds through the streets and passersby cheer and wave the peace sign.

Quentin Somerville/BBC

Quentin Somerville/BBCThe new Syrian flag, with its green stripe instead of red, and three red stars instead of two green, has become a common sight on shop doors and hanging from balconies. But in the upper areas, people mostly watch in silence as the caravan moves on. There are fewer new flags in evidence.

Azzam al-Ali, 28, a security officer with Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham from Deir al-Sur in eastern Syria, sits in the front seat. He says that after all this repression, it will take some time for people to trust authority again.

“Most of the persecuted people who come with complaints are from two sects, Sunnis and Alawites. We don’t differentiate. But the extreme poverty that this regime left behind has caused this huge chaos,” he tells me as the convoy parts in traffic.

He points out that Alawites, some of whom were among the poorest of the poor in Syria, also suffered under the Assad regime.

We arrived at Nour’s apartment and six armed men from Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham rushed up the stairs.

Darren Conway/BBC

Darren Conway/BBCThe woman behind the door refuses to open the door, but after some negotiation he opens the door, ordering her and her family to leave. Nour enters to bring some clothes and books for her daughter, who is studying for exams. Weapons and ammunition owned by the rebels were confiscated.

“When I went to Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham today, I felt terrified,” Nour says. “They were very creepy and scary looking. But honestly, they were very cute.”

But she won’t go back to the apartment. She says: One nightmare in Syria has ended, and another nightmare has begun for the Alawites.

As she clutches her belongings, Nour says she no longer feels safe in her home.

“It is impossible for me to live here again. I have hope, but not in the near future. At the moment I don’t dare.”

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/1024/branded_news/0d4b/live/3094c050-bbbe-11ef-aff0-072ce821b6ab.jpg